Introduction

Patient–ventilator asynchronies (PVAs) are frequent events during invasive mechanical ventilation, with reported incidences ranging from 25% to 93%, depending on the population studied and the sensitivity of detection methods.1–4 These disturbances in patient–ventilator interaction are far from benign: they have been linked to adverse clinical outcomes, including prolonged duration of ventilation, extended intensive care unit (ICU) stays, and increased morbidity and mortality.5 The impact of these outcomes appears to depend not only on the frequency of asynchronies but also on their intensity, duration, and persistence over time.6

Despite decades of research on this phenomenon, most studies have concentrated on intrinsic factors such as ventilator mode, pulmonary mechanics, and the depth of sedation.7–9 Nevertheless, important gaps remain in our comprehensive understanding of PVAs,10 particularly regarding the influence of routine clinical interventions on patient–ventilator synchrony. Essential ICU practices, such as oral hygiene, airway suctioning, patient repositioning, and intrahospital transport, may transiently disrupt respiratory mechanics and trigger episodes of asynchrony, especially in patients with partial spontaneous breathing or limited physiological reserve.

Several authors have highlighted that many asynchronies remain undetected in daily clinical practice, either because of their transient nature or the absence of continuous waveform monitoring. These events have been documented to occur at any phase of the ventilatory cycle, underscoring their clinical variability and complexity.11–13

In this context, the hypothesis that common clinical practices may unintentionally trigger PVAs represents a scarcely explored avenue of research. Although this phenomenon has been empirically acknowledged by experts in ventilator monitoring, no visual reports documenting its occurrence exist, nor are there studies directly linking it to specific routine care interventions, an important gap in our current understanding of patient–ventilator interaction.

The aim of this observational exercise was to document, through real-time graphical monitoring, the occurrence of unintentional asynchronies triggered during common clinical interventions in critically ill patients. A clinical phenomenon frequently perceived but not formally described in the specialized literature. In addition, a structured literature review was conducted to contrast and corroborate that this phenomenon has not been identified or reported as a potential cause of asynchrony in either current or previous reviews.

Methods

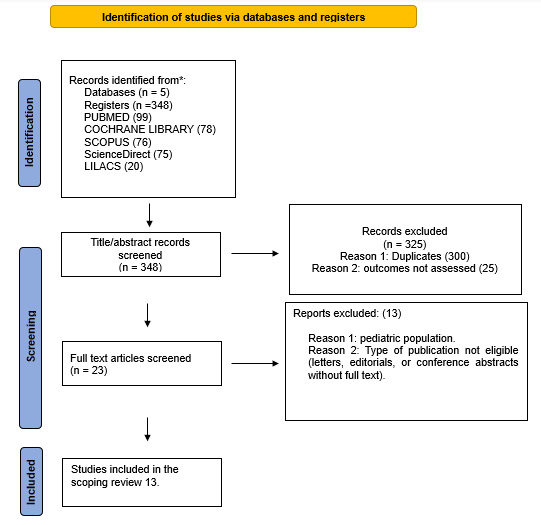

This review followed the PRISMA-ScR checklist (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews)14 and was guided by the methodology developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). The process included the following stages: formulation of the research question, identification of relevant studies, study selection, data extraction, synthesis and presentation of the results, and conclusions.

Research Question

This scoping review was guided by the PCC (Population, Concept, Context) framework, as recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI):

Population (P): Adult patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation.

Concept (C): Patient–ventilator asynchronies (PVA) induced by routine clinical practices (e.g., endotracheal suctioning, oral hygiene, patient repositioning, intrahospital transport).

Context (C): Hospital intensive care settings, including general and specialized ICUs.

Eligibility Criteria

The literature search was conducted in accordance with the proposed research question. We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), descriptive or analytical observational studies, and systematic or narrative reviews that reported or described any type of PVA, regardless of whether it was induced by routine clinical practices. This broad approach was adopted to contrast the existing evidence and to identify the absence of studies explicitly addressing asynchronies induced by common care interventions. Given that no primary studies on this phenomenon were found, narrative reviews were included to ensure a comprehensive mapping of what has and has not been investigated in the field, in line with JBI guidance for scoping reviews. No restrictions were applied regarding the year of publication. Articles published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese were considered eligible.

Two independent investigators (AMEP, HMPG) screened titles and abstracts and assessed full texts for eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or, if necessary, by consultation with a third reviewer.

Exclusion Criteria

We excluded studies that did not involve adult patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation in an ICU setting. Studies focusing exclusively on non-invasive ventilation or pediatric populations were also excluded. Furthermore, we did not consider editorials, letters to the editor, expert opinions lacking primary data, or conference abstracts without full-text availability.

Information Sources

A comprehensive search was conducted in five electronic databases: Scopus, ScienceDirect, PubMed, LILACS, and the Cochrane Library. The search strategy incorporated both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Descriptores en Ciencias de la Salud (DeCS). The primary search terms included: “Asynchrony” OR “Patient–ventilator asynchrony” OR “Patient–ventilator dyssynchrony” AND “Critical care” AND “Mechanical ventilation.” In addition, the reference lists of the included studies were manually screened to identify further eligible articles.

Search Strategy

The research question was formulated using the PCC framework (Population, Concept, and Context), in accordance with Joanna Briggs Institute guidance. We combined controlled vocabulary (MeSH and DeCS) with free-text terms in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Database-specific search equations were developed in collaboration with an information specialist to ensure precision, comprehensiveness, and adequate coverage.

Duplicate records were removed, and study selection was performed in Rayyan15 (Rayyan Systems Inc., Doha, Qatar) to enable blinded, independent screening by two reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or, when necessary, by a third reviewer. Screening proceeded in two stages (titles/abstracts, then full texts) against predefined eligibility criteria; studies meeting all criteria were included. The complete search equations for each database are provided in the Supplementary Table S1.

Data synthesis and extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers using a standardized template specifically designed for this review. The extraction table included the following items: author, year of publication, study design, types of PVA, and reported causes of asynchronies. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by consensus or, when necessary, by consultation with a third reviewer.

The extracted data were organized into structured evidence tables to allow comparison across studies and to highlight gaps in the literature. This process facilitated both the descriptive mapping of existing evidence and the identification of the absence of studies reporting asynchronies induced by routine clinical practices.

Observational Analysis

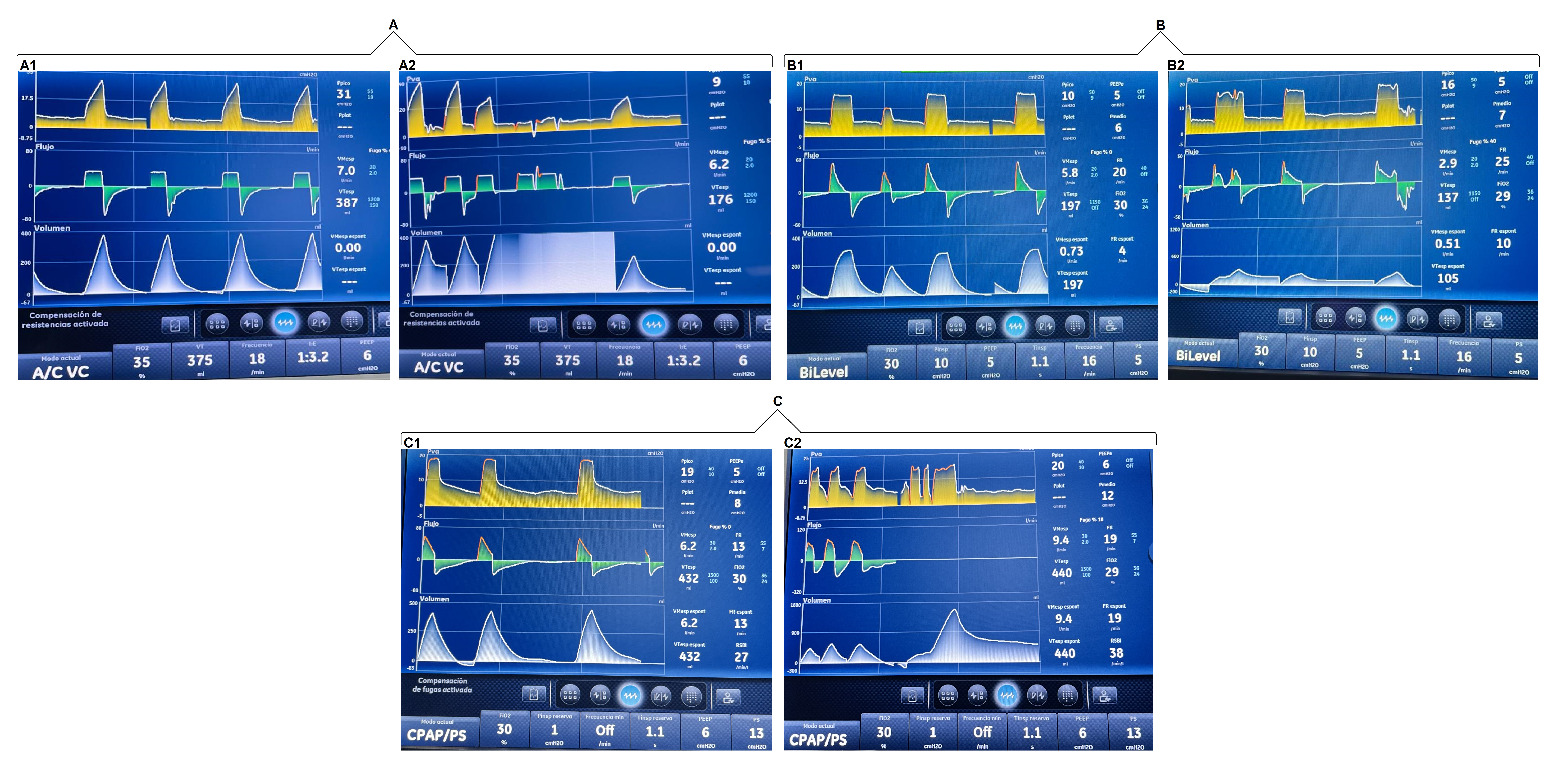

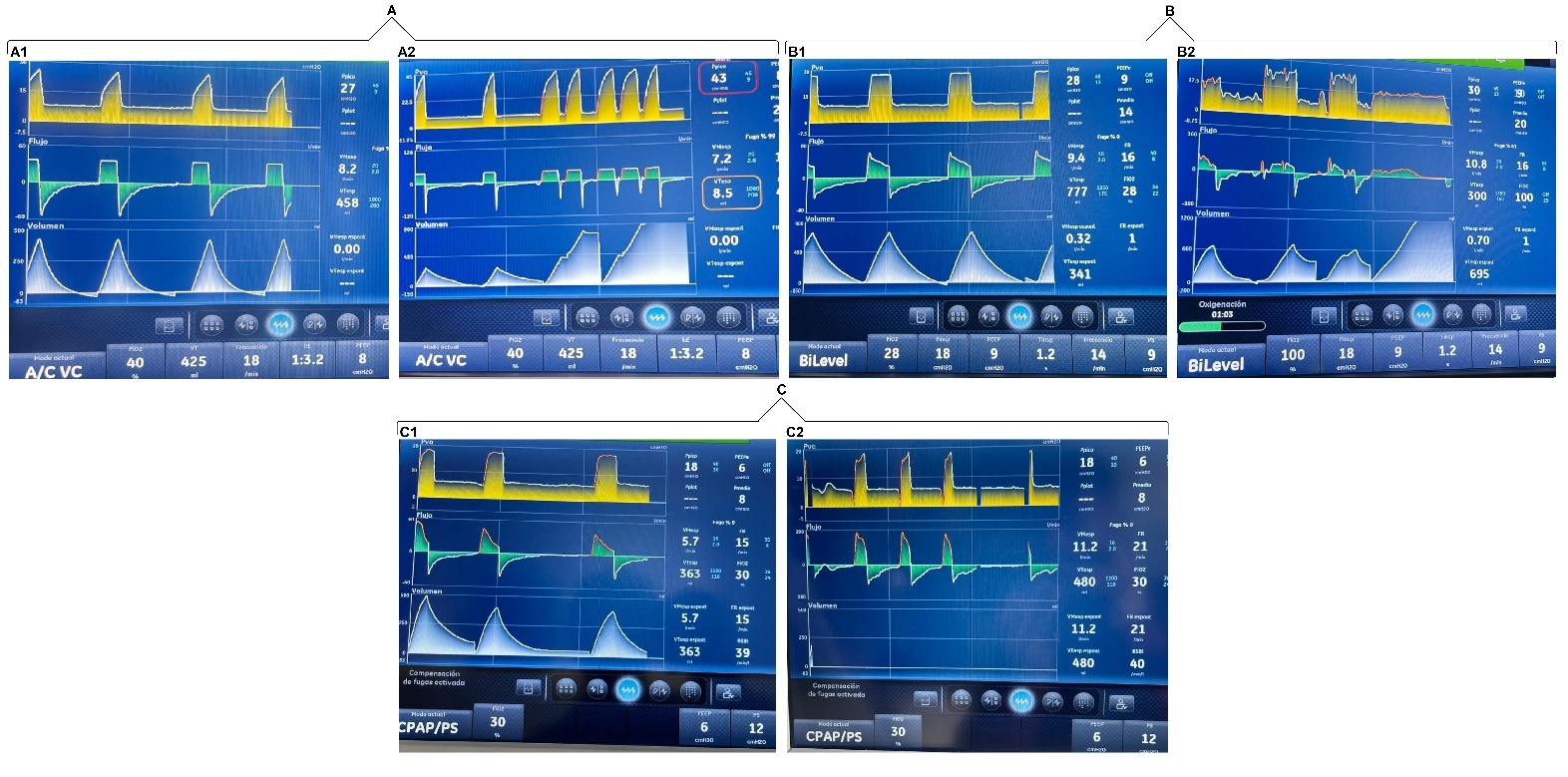

To document the occurrence of unintentional PVAs, a systematic observational assessment of ventilator waveforms was conducted in patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation. Waveforms were analyzed during three types of routine clinical interventions performed in the ICU. Asynchronies were identified and recorded through continuous graphical monitoring of pressure, flow, and volume curves across different ventilatory modes, without modifying the parameters previously set by the responsible clinical team.

In our unit, physiotherapists (PTs) with ICU training are responsible for both invasive and non-invasive ventilatory support. This includes ventilator assembly, programming, and continuous monitoring. The mechanical ventilator used was CARESCAPE™ R860.

This observational component followed a naturalistic, descriptive design. No clinical variables such as sedation level, disease severity, ventilator-related factors beyond routine settings, or provider expertise were controlled or manipulated, as the objective was to document real-world patient–ventilator interactions during usual care. Accordingly, the observational findings are descriptive and exploratory, intended to generate preliminary visual evidence rather than establish causal relationships.

The analysis was structured around three commonly encountered care scenarios:

Interventions related to respiratory care

In patients with an artificial airway, ensuring the appropriate delivery of the programmed tidal volume is essential. This section examined the asynchronies observed during procedures such as oropharyngeal suctioning, oral hygiene, and airway clearance manoeuvres. These procedures were performed by the PT on duty.

Assisted postural changes

Patients receiving sedoanalgesic agents often have limited mobility and therefore require external assistance for repositioning and mobilization. We documented asynchronous events triggered during routine passive mobilization aimed at preventing complications associated with prolonged immobility. The postural changes were carried out by the nursing assistants, and the ventilatory graphs were analyzed by the PT.

Intrahospital transport

During transport for diagnostic or therapeutic procedures within the facility, PVA episodes were identified at specific moments, such as navigating ramps, entering lifts, or repositioning during connection and disconnection from external support systems. In this section, the PT on duty was present throughout the entire transfer, from departure to return to the cubicle, ensuring the artificial airway and monitoring the ventilatory waveforms.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Research Committee of the SES Hospital Universitario de Caldas under Record CI dated 28 August 2025.

Results

In the initial search, 348 articles were retrieved from five databases. After removing 300 duplicates and excluding 25 articles, 13 studies remained and were included in our review (Figure 1).

Characteristics of the included studies

The selected studies were published between 2000 and 2025, with the highest number appearing in 2018.20–22 Regarding methodology, the most frequently employed approach was the narrative review.16,18–28 In contrast, only one prospective study was identified.17

Reported patient–ventilator asynchronies

The most frequently reported PVAs, in relation to their underlying causes, were Ineffective Triggering16–18,20–24,26–28 and Delayed Cycling, and Premature Cycling.18–28 Only three publications documented all categories of PVAs24,26,28 (Tables 1 and 2).

Graphical analysis of ventilator waveforms during three different interventions

The patients included in the analysis presented a range of predominant critical conditions, mainly respiratory, neurovascular, renal, and surgical. The most commonly used sedative and analgesic medications were midazolam, fentanyl, dexmedetomidine, and propofol.

In terms of timing, as the interventions analyzed corresponded to routine clinical care, respiratory procedures, specifically airway clearance, had a maximum duration of 3 minutes. Postural changes, performed every 3 hours, typically lasted between 5 and 8 minutes. In contrast, intrahospital transfers were more time-consuming; from the moment the patient left the unit until their return, the duration could vary between 15 and 20 minutes.

With regard to the PVAs, these were short in duration, as they were transient and tended to be exacerbated during routine clinical care. They were observed for a maximum continuous period of 1 minute. The PT on duty made adjustments when necessary; however, in most cases, no intervention was required, as once the stimulus provoking the asynchrony ceased, the patient returned to ventilatory synchrony.

We found that induced asynchronies may occur independently of the ventilatory mode and that double triggering was observed across all three interventions (Figures 2, 3, and 4).

Discussion

Our findings provide compelling evidence that routine clinical interventions, such as patient mobilization and endotracheal suctioning, can transiently yet consistently trigger PVAs. Although these interventions are essential components of care in patients receiving invasive ventilatory support, their unintentional impact on patient–ventilator interaction has been overlooked, likely due to the absence of literature explicitly addressing this phenomenon. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to document the presence of induced asynchronies through real-time waveform analysis.

To clarify the scope of our observations, we have emphasized that the graphical analysis aimed to document a real-world clinical phenomenon rather than establish causal inferences. The transient nature of these induced asynchronies required a descriptive, naturalistic design aligned with routine ICU practice.

In our structured review, despite covering an extensive 25-year period, none of the published studies identified routine clinical interventions as direct or indirect contributors to PVAs, representing a critical omission. Several factors may explain this gap. From the early use of negative-pressure ventilation with the “iron lung,” graphical monitoring was unavailable, and even the first positive-pressure ventilators lacked such functionality, making it difficult to identify the causes of PVAs. In this context, Harrison (1962) appears to have been the first to introduce the concept of patient–ventilator interaction, whereas Branson (2011) provided a comprehensive update on PVAs over the preceding 40 years. However, the notion of asynchronies induced by routine clinical practices was not mentioned.29–31 This reinforces that our findings should be interpreted as preliminary visual evidence within a field where methodological gaps persist, and not as results derived from a controlled comparative design.

At present, the interventions analyzed are considered essential and are performed several times a day. For example, Jongerden et al.32 reported that airway clearance procedures may be performed 8-17 times per day, potentially increasing the incidence and severity of asynchrony episodes in mechanically ventilated patients. In our study, ventilator waveforms were synchronous before the interventions, with PVAs consistently occurring during all three. By documenting and demonstrating this omission against the evidence, we confirm its lack of recognition in the literature and establish this previously unconsidered cause.

This observation carries important clinical implications. Over the past two decades, considerable efforts have been made to elucidate the aetiology and consequences of PVAs. Seminal works by Blanch et al.2 and Kyo et al.5 have demonstrated associations between PVAs and adverse outcomes, particularly when the asynchrony index (AI) exceeds 10%. In our study, we observed AI values greater than 10% in volume-controlled modes, a threshold linked to poor clinical outcomes, further reinforcing the need to examine how routine care practices may inadvertently disrupt patient–ventilator synchrony. Although these observations suggest potential physiological relevance, we acknowledge that the exploratory design of this study does not permit the determination of causality or the quantification of risk.

Several authors, including Habtamu et al.10 and Alcântara et al.,11 have highlighted major gaps in knowledge regarding patient–ventilator interaction. They also emphasize that many PVAs go undetected in routine practice owing to limited training, insufficient monitoring, or inadequate waveform interpretation. We extend this concern further: these events are not only overlooked, but their clinical significance may also be systematically underestimated. This is particularly concerning given that potentially life-threatening PVAs, such as double triggering, were observed in our study during intrahospital transport.

Saavedra et al.25 have described multiple types of lung injury associated with PVAs, including increased respiratory workload, reduced patient comfort, and an elevated risk of patient self-inflicted lung injury (P-SILI). We observed such phenomena in patients on pressure support ventilation, in which the number of spontaneous breaths increased during interventions, potentially increasing respiratory workload.

Our study provides a comparative perspective across three ventilatory modes, demonstrating that asynchronies can occur regardless of the selected mode. This represents a meaningful step forward in understanding PVAs in real-world clinical scenarios. Another contribution of our manuscript is that it highlights an ongoing challenge for professionals responsible for ventilatory support. As visually documented, PVAs may occur at any time, even during critical situations such as intrahospital transfers. This underscores the need for staff not only to develop the ability to accurately identify asynchronies but also to intervene promptly whenever they arise, thereby ensuring consistent delivery of lung-protective ventilation.

By documenting these induced asynchronies, we introduce a novel research area with direct implications for patient safety. Since such clinical interventions are unavoidable, it becomes essential to evaluate how they are performed. Future research should therefore focus on developing integrated care protocols aimed at minimizing transient ventilatory disruptions, ultimately improving the quality and safety of mechanical ventilation.

It is important to note that this observational exercise did not control for clinical variables such as sedation level, disease severity, provider expertise, or ventilator-related factors beyond routine practice. These aspects were intentionally not manipulated, as the objective was to capture real-world interactions under usual care conditions. Accordingly, the findings should be viewed as descriptive rather than causal.

Although our small sample size is an acknowledged limitation, we believe this report provides an essential foundation for further investigation. An additional limitation is that most of the available literature on PVA consists of narrative reviews rather than primary studies. While this reflects the weakness of the existing evidence base, it also highlights a key finding of our work: across more than two decades of publications, no study, primary or secondary, has identified routine clinical interventions as potential contributors to PVA. This gap underscores the need for larger, methodologically robust studies to quantify the prevalence and impact of this phenomenon, explore its pathophysiological and prognostic implications, and inform strategies that promote safer, more synchronized, and patient-centred mechanical ventilation.

For this reason, we have revised the manuscript to frame these observations as an initial foundation rather than definitive evidence. By documenting a previously undescribed phenomenon and clarifying the exploratory nature of our approach, this study provides an early step towards understanding the potential effects of routine clinical interventions on patient–ventilator interaction. Importantly, it also highlights the need for more robust and controlled research designs capable of determining the prevalence, mechanisms, and clinical significance of these induced asynchronies.

Conclusion

Patient–ventilator asynchronies have been extensively studied in relation to ventilatory modes, pulmonary mechanics, and sedation depth. However, our observational analysis provides preliminary visual evidence of an aspect not previously documented in the literature: the occurrence of transient asynchronies associated with routine clinical interventions in the ICU. These findings suggest that essential care practices may briefly disrupt patient–ventilator synchrony, particularly in patients with limited physiological reserve.

In parallel, the scoping review identified a long-standing gap in the evidence: over more than two decades, no primary studies have explored routine clinical interventions as potential contributors to PVAs. This absence underscores the need to investigate how procedures such as airway hygiene, repositioning, or intrahospital transport may influence patient–ventilator interaction.

Given the descriptive and naturalistic design of the observational component, these findings should be interpreted with caution and not as causal inferences. More robust and controlled studies are required to quantify the prevalence of these induced asynchronies, examine their physiological determinants, and clarify their clinical significance. Nonetheless, the present work provides an initial foundation for a new line of inquiry and highlights the opportunity to design strategies aimed at preserving ventilatory synchrony during unavoidable components of critical care.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form and declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Research Committee of the SES Hospital Universitario de Caldas under Record CI dated 28 August 2025.

AI Statement

The authors confirm that no generative AI or AI-assisted technology was used to generate content.