Background

Over 1 million healthcare professionals are currently ensuring services to more than 38 million people living in Canada.1 Among them, approximately 12,200 respiratory therapists (RTs) play a vital role in delivering essential care to patients with chronic and acute cardiopulmonary issues across all age groups and in various practice settings, ranging from home ventilation care to neonatal intensive care.1 Despite the widespread presence of RTs in the Canadian healthcare system, the critical nature of their work, and their diverse roles, there are very few studies that describe the profiles of RTs in Canada.2 The available literature often focuses on discrete tasks that RTs might perform, such as using high-frequency jet ventilation3 or performing endotracheal intubation.4 These studies overlook the need to understand the broader scope of the profession in the Canadian context. Descriptive data about the emerging roles of RTs in countries outside of North America (e.g., China, India) exist5,6; however, data from these international studies may not be comparable with the Canadian healthcare system considering its unique characteristics, such as a publicly funded, universally accessible system,7 and differences in educational and practice standards among healthcare professionals.8 Alongside their clinical duties, RTs are expected to be aware of and effectively integrate emerging high-quality scientific evidence into routine practice to ensure patients receive the most up-to-date care. The knowledge, attitudes, behaviours, and skills associated with integrating evidence into practice are encompassed within a competency referred to as scholarly practice.

Scholarly practice is broadly understood as a process whereby clinicians engage with and apply multiple sources of knowledge (i.e., experiential, research evidence) in ongoing, critical, reflective and evaluative ways in their daily practice.9–14 Engagement in scholarly practice has been associated with several positive outcomes, such as professional empowerment and role satisfaction, a positive work environment, as well as improved care delivery and patient outcomes.15–19 Further, a recent qualitative study of 26 RTs shed light on the multifaceted nature of scholarly practice.20 Many participants conveyed that scholarly practice encompassed a wide range of activities and skills, including, but not limited to, conducting research, reflective thinking, research literacy, knowledge translation, the ability to identify gaps in professional knowledge, and to contribute to advancing the profession and healthcare field. Moreover, the participants discussed how engaging in scholarly practice could elevate the status of respiratory therapy as a profession. It enhances the self-image and professionalization of respiratory therapy, which, in turn, augments its legitimacy and credibility amongst the interprofessional team and the public.20 Collectively, these activities, skills and behaviours are likely to foster a deeper appreciation for the respiratory therapy profession and encourage RTs’ continued engagement in their profession, potentially reducing attrition21 and burnout rates.22–24 Nurturing practitioners’ dedication towards their profession may also translate into improved patient outcomes and enhanced quality of care.25

Despite the recognized benefits of engaging in scholarly practice, a growing body of evidence indicates that many clinicians in various professions lack adequate preparation and confidence to fulfill this role effectively.26–30 This is particularly noticeable in respiratory therapy, as this competency is not explicitly included in their competency framework,31,32 suggesting that this competency is superficially— if at all— taught and assessed during entry-level education. Consequently, graduates may not fully grasp the importance of scholarly practice or possess the necessary knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours to implement it in their practice.

A comprehensive understanding of the current state of the practice and scholarly profile of the respiratory therapy profession can help stakeholders such as policymakers, decision-makers, professional associations, scholars, employers, and patients to have a clearer understanding of the value and significance of RTs in healthcare. For example, documenting factors such as gender distribution, years of experience, practice locations, engagement in research, and accomplishments in scholarly activities is essential for professional associations to shape their strategic planning efforts,33–35 educators to design and refine curricula to match the evolving needs of the profession and healthcare system, and offer RTs opportunities to enhance their skills and expertise.36 Moreover, this knowledge can provide evidence to inform public policy development, including regulatory requirements, scope of practice guidelines, and workforce planning strategies to ensure that RTs can effectively meet the needs of patients and communities.37 The overall aim of this study was to describe the demographic characteristics and scholarly and practice profiles of the respiratory therapy profession in Canada.

Methods

Study Design

We administered a cross-sectional survey to a convenience sample of Canadian RTs. The results are reported using the Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS).38

Participants & Recruitment

We aimed to recruit a convenience sample from the pool of 12,291 registered Canadian RTs. To achieve this, we invited all members of the Canadian Society of Respiratory Therapists (CSRT) or their respective Canadian provincial regulatory body39 who agreed to be contacted for research and had a valid email address to participate in this study. To be eligible to participate, RTs had to: 1) hold a valid credential or license to practice in Canada; 2) be employed either part-or-full-time; and 3) be able to read in either English or French. We excluded students, retired RTs and licensed RTs practicing outside of Canada because they could not provide information regarding their current practice.

We recruited participants using two parallel methods to optimize response rate and minimize the potential for selection bias.40 Recruitment emails were sent through both the CSRT and the nine provincial regulatory bodies’ email lists, considering that membership to the CSRT is voluntary. The first author (MZ) sent an email explaining the purpose of the study, the research team’s contact information, the consent form, and a recruitment poster (which included a link and QR code for the study) to the director of the national association and every provincial regulatory body. Each director either chose to circulate the email to their professional member list or include the recruitment poster in their regular communications to their members.

Data Collection

The survey was mounted onto the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) survey platform, which assigns each participant a unique identification number to ensure anonymity. The survey link was then distributed through the CSRT and regulatory bodies’ email lists. The survey was open from November 1 to December 20, 2023 (7 weeks in total), coinciding with all the communications the CSRT and regulatory bodies had planned to send to their members. Reminders were sent at two, four and six weeks after the initial email.

Instrument

The survey consisted of an online questionnaire that was based on the findings of a related scoping review41 and a qualitative study20 exploring what scholarly practice means and how it manifests in practice from the perspective of RTs. The survey was created following best practice guidelines42 and a detailed description of its development is currently being prepared for publication. Briefly, the scoping review results informed the semi-structured interview guide for the qualitative interpretive description study.41 The participants’ excerpts from the qualitative study provided the foundation for crafting the survey items. The full team participated in creating and reviewing the items. The draft survey was then shared with three content and three measurement experts outside the research team to gain feedback on wording of the items, clarity, suggest changes and overall length. Once the feedback was integrated, the survey was mounted on REDCap and pilot-tested with 81 participants to provide evidence of validity for the survey. Following the pilot results, we updated the survey and professionally translated it to French.43,44

The final survey contained seven sections, with a total of 52 items. Section 1 contained six items exploring scholarly activities, such as the number of papers read, funding received to conduct research, and the number of scientific presentations given. Section 2 contained nine items focused on the identity of a scholarly practitioner in respiratory therapy, mentorship, supervision of students, and critical appraisal of the literature. Section 3 included eight items on the factors (positive and negative) that might influence scholarly practice, such as knowledge of research methodology, a supportive work environment and availability of resources. Section 4 contained six items about participants’ perceptions regarding the image and legitimacy of the respiratory therapy profession, the level of respiratory therapy education and RTs’ standing amongst the interprofessional team. Section 5 contained seven items about how scholarly practice might influence the respiratory therapy profession, about using research to advocate on behalf of patients, and about the feasibility of scholarly activities during practice. Section 6 contained two open-ended questions about benefits and challenges of scholarly practice, and section 7 contained 10 items about demographics.

Participants indicated their responses to section 1 by estimating percentages or by giving a numerical value (e.g., I read 10 empirical papers in a regular month). Sections 2 to 5 were answered using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (6). Section 6 contained two open-ended questions related to scholarly practice, "Please list 2-3 benefits of being or becoming a scholarly practitioner" and "Please list 2-3 of the most significant challenges you’ve encountered/anticipate in becoming a scholarly practitioner." Supplementary File 1 contains the full survey.

Research Ethics

This study was approved by the McGill University’s institutional review board (study number A01-E04-22A). Informed consent was obtained through accepting the survey link, completing, and returning the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

During the data collection phase, our survey was shared on social media via a third party. Soon after the survey launch, we noticed the response rate increased rapidly (>200 responses within minutes). We paused the survey to review the responses and determined that our survey was targeted by spambots and/or non-eligible participants seeking the participation incentive. We re-opened the survey link after 24 hours, asked participants not to share the link (either personally or via social media) and created a protocol to clean the data before analysis. See Supplementary File 2 for full details about the data cleaning procedure.

Data analysis involved reporting continuous variables as means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and proportions. Data collection, retrieval and generation of descriptive statistics were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Each open-ended question was analyzed using summative content analysis, which starts with attributing a code to each statement, collapsing similar codes into categories and counting the frequency of different codes and categories to identify patterns, themes and trends across the data.45

Results

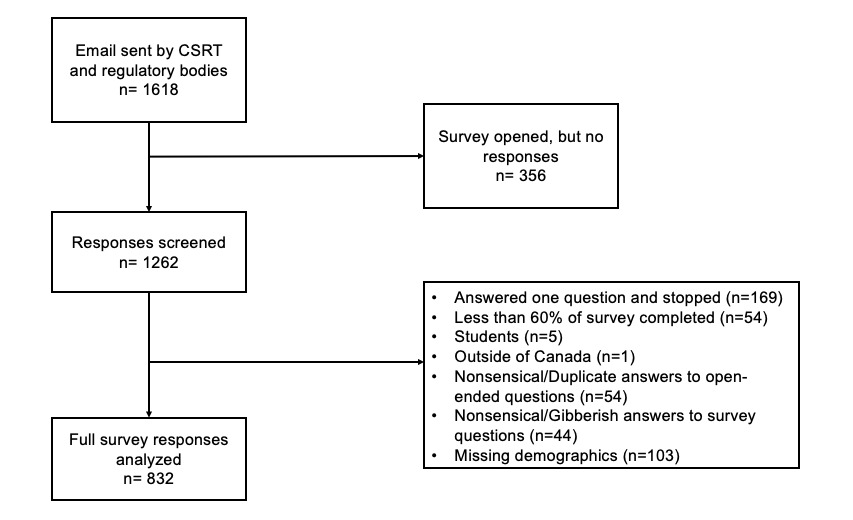

The full survey was accessed 1618 times. After removing fully incomplete data, students, participants outside of Canada, duplicates and cleaning the data, we analyzed full survey data from 832 participants. The response rate was 6.8% (Figure 1).

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 presents demographic information. Most of the respondents were from Ontario (17.8%; n=148), Québec (15.7%; n=131), and Alberta (13.3%; n=111). A large proportion of respondents self-identified as white (81.6%; n=703), women (75.2%; n=627) and were between the ages of 30 to 39 (34%; n=283). Most participants had completed an undergraduate degree (above their respiratory therapy diploma) as the highest educational attainment (39.9%; n=332). One-third (33.3%; n=277) of participants reported that their respiratory therapy professional diploma was their highest level of education. Few participants were enrolled in graduate studies (13.6%; n=113).

Scholarly activities

Table 2 presents common scholarly activities in which RTs engaged in. 12.1% had received some form of financial support for engaging in research activities and few participants had authored or co-authored any peer-reviewed publications (mean=0.64; SD=3.9). Additionally, RTs reported reading an average of 2.2 (SD = 3.8) peer-reviewed publications each month. Of the participants who reported attending online or in-person conferences in the last 12 months, 72% (n=597) attended an average of 4.1 (SD=7.3) presentations locally and 39.2% (n=326) attended an average of 1.0 (SD=2.7) provincial conference. Finally, of the participants who reported giving scientific presentations, 20% (n=166) gave an average of 1.0 (SD=5.5) presentation in a local setting and 9.5% (n=79) gave an average of 0 (SD=2.0) presentations at provincial conferences.

Practice Profile

Table 3 describes respondents’ practice profile. The majority of respondents worked full-time (82%; n=682). Over two-thirds (69.7%; n=580) worked in an urban setting, and less than half (45.3%; n=377) worked in a tertiary care hospital. In a typical week, respondents spend an average of 17.6% of their time working in adult intensive care units, followed by 13.1% of their time in community and primary care and 11.6% in anesthesia. In contrast, they spent a small portion of their time in research (1.5%), marketing and sales (1.1%), and clinical support for industry (0.8%). Respondents often distributed their time across multiple practice areas. See Supplementary File 3 for the distribution across practice locations.

Scholarly Practice (Section 1): The identity of a scholarly practitioner in RT

Table 4 (section 1) summarizes the results regarding RTs’ views of what a scholarly practitioner looks like and what sets them apart in the respiratory therapy profession. Most respondents (93.1%; n=793) either agreed or completely agreed that being able to critically reflect on one’s practice is an important part of being a RT. Further, a large majority of respondents agreed or completely agreed that having a mentor helps RTs become scholarly practitioners (81.8%; n=681), and that taking the time to mentor other RTs (78.2%; n=651) and to supervise students (86.9%; n=723) are important for developing a scholarly practitioner identity.

Scholarly Practice (Section 2): Factors supporting scholarly practice

Table 4 (section 2) contains the responses regarding the circumstances that influence the development of scholarly practice or its enactment. Most respondents agreed or completely agreed that the following are necessary for developing as a scholarly practitioner: having a supportive work environment (93.4%; n=777), access to resources (e.g., funding opportunities, protected time, online databases, CPD opportunities) (82.8%; n=689) and possessing the skills to apply research findings into practice (78.6%; n=654). Conversely, slightly over one-third of the respondents (35%; n=288) disagreed that having access to higher education (e.g., MSc. PhD) is necessary for developing as a scholarly practitioner.

Scholarly Practice (Section 3): The image and legitimacy of the RT profession

Table 4 (section 3) contains the results on the self-perceived image, legitimacy and value of the respiratory therapy profession. While 73.4% (n=611) of respondents agreed or completely agreed that RTs are valued members of the interprofessional team, just over half (53.1%; n=442) agreed or completely agreed that RTs would be more valued as part of an interprofessional team if they held an undergraduate degree (e.g., BSc.RT., BRT) or that the entry-to-practice qualification for RT should be an undergraduate degree (56.9%; n=473).

Scholarly Practice (Section 4): Scholarly practice influencing your practice

Table 4 (section 4) summarizes the results related to the relationship between RTs’ bedside clinical practice and scholarship/academic research. Most respondents (78%; n=649) agreed or completely agreed that understanding research enables them to advocate on behalf of patients, and that clinical work is necessary for generating research questions in respiratory care (78%; n=646). Two-thirds of respondents agreed or completely agreed that research findings are useful in their day-to-day practice (67.3%; n=560), and participating in scholarly activities (such as research, quality improvement, program evaluation) enabled them to better understand the connection between research and clinical practice (65.8%; n=548).

Open-ended questions

Over two-thirds of participants provided a response to the open-ended questions: "Please list 2-3 benefits of being or becoming a scholarly practitioner" (67.5%; n=562) and "Please list 2-3 of the most significant challenges you’ve encountered/anticipate in becoming a scholarly practitioner" (66.8%; n=556). 8.2% (n=217) of respondents reported that the benefit of being or becoming a scholarly practitioner is to provide more efficient and better patient care and 22.9% (n=278) responded that the most significant challenge encountered or anticipate in becoming a scholarly practitioner is the lack of time (Table 5).

Discussion

This study described the practice and scholarly profile of a subset of RTs in Canada. Overall, our data suggest that scholarly practice among this group is limited; very few RTs publish peer-reviewed work, participate in conferences, and an equally small number give scientific lectures. There is a recognition of the importance of critical reflection, receiving mentorship, and mentoring others in developing a scholarly practitioner identity; however, there are challenges related to accessing resources and higher education to support aspects of scholarly practice. Furthermore, there is a discrepancy among participants about the perceived value of RTs within interprofessional teams as well as about having an undergraduate degree as entry-to-practice.

In our sample, 75.5% of respondents reported being below 49 years of age, and half of our sample indicated working in the profession for 15 years or less. These data are consistent with national registries on the respiratory therapy profession.46–50 Our findings suggest that the respiratory therapy profession is relatively young. Similar to many young and emerging healthcare professions (e.g., physician assistants), clinicians transitioning into scholarly roles have not yet had the time or expertise to conduct empirical research to establish a robust evidence base for their profession.51 However, if given the opportunity to engage in research, RTs’ roles may expand, much like it has with nurses and pharmacists who now have prescribing privileges, as one example.52,53 Such role expansion could positively affect the profession by creating new job opportunities, such as telehealth and physician extender roles, that enable RTs to provide more specialized care, thereby enhancing the overall quality of care.54,55

The gender distribution of our sample aligns with national registries on the respiratory therapy profession,46–50 with approximately 75% of our respondents identifying as women. Given that female healthcare professionals may be less involved in various aspects of scholarly practice, such as publishing papers and receiving research grants,56–59 further studies are needed to explore how gender stereotypes affect scholarly practice at both the professional level (e.g., power imbalances with male physicians despite having a strong scientific foundation)60,61 and the personal level (e.g., parenthood, home caregiver roles post-pandemic).62,63 These studies could help design strategies to create a more inclusive environment for scholarly practice within the respiratory therapy profession.

Similarly, our survey results show a higher proportion of respondents identifying as white (81.6%) compared to other races, such as Indigenous (3.0%), South Asian (2.7%) or East Asian (2.6%). Future research should systematically investigate whether the profile of the respiratory therapy profession in Canada resembles the general population they are providing care for.64

The results of this survey indicate that scholarly practice among RTs in Canada is limited. Respondents reported infrequently reading peer-reviewed publications, rarely participating in the writing of scientific manuscripts, receiving minimal financial support for engaging in research activities, and few presented at scientific conferences. While the reasons for the lack of engagement in such activities are unclear, we can surmise that RTs may not be taking an active role in driving their own learning, relying instead on knowledge and education from other professions, such as medicine or physiotherapy. This reliance on other professions may not fully account for the unique nuances of respiratory therapy practice.51,65,66 Based on our findings, RTs typically read an average of 2.2 articles per month. While this figure might initially appear low, it aligns with reading habits observed in other rehabilitation professions (e.g. occupational and physiotherapists), which typically range between 2 to 5 articles per month.67,68 Also consistent with other rehabilitation professionals, RTs in this study frequently cited time constraints and limited access to resources (e.g., articles, professional activities) as primary barriers to reading research. In contrast, physicians typically read a significantly higher volume of articles, averaging between 12 to 15 articles per month.69 However, it’s important to note that these statistics are derived from older literature, and accessing research and the volume of research available has changed significantly since then. Recent observations highlight the overwhelming challenge of keeping pace with the ever-expanding body of research in health. For instance, there has been a 20-fold increase in the number of systematic reviews published between 2009 and 2019; this is equivalent to 80 new systematic reviews per day.70 These numbers highlight the importance for clinicians to rely on guidelines and other evidence-based knowledge sources (e.g., Cochrane Podcasts, HealthEvidence.org), to stay abreast of current literature.71–73 Nevertheless, the impact these sources of knowledge will have on professionals’ practice depends on them possessing a fundamental understanding of research evidence.74,75 Unfortunately, this is currently not the case in the respiratory therapy profession; though scholarly practice is not included in respiratory therapy competency frameworks, participants have expressed a desire to enhance their abilities.

For the most part, respondents’ primary work responsibilities entailed full-time direct clinical care, with very few reporting involvements in marketing, clinical support for industry or research. Additionally, only a minority hold a research degree (e.g., MSc, PhD), and most respondents are not currently enrolled in post-professional education. This may be concerning as it suggests that only a small number of RTs have the required competencies to produce research at a level that would advance the respiratory therapy profession, enabling RTs to adapt to evolving healthcare needs and deliver optimal patient care.76 Addressing this challenge requires innovative strategies to enhance the research capacity within the respiratory therapy profession. One approach could involve establishing a community of practice for RTs who are actively engaged in research. Such communities are recognized for their effectiveness in enhancing research skills and facilitating the sharing of evidence-based practices.77 Another approach could be creating and implementing a mentoring program where experienced researchers (be they RTs or other professionals) are paired with those looking to enhance their research skills.78 Finally, it would be important to systematically create a research agenda through a consensus process to guide funding allocation decisions.51,79,80 Given the identified challenges in research capacity within the respiratory therapy profession, exploring innovative solutions to empower RTs to contribute meaningfully to advancing the profession is imperative.

While respondents generally agreed on questions about the identity of a scholarly practitioner, the factors supporting scholarly practice and how it influences practice, participants’ responses regarding the image, legitimacy and education in the respiratory therapy profession were more varied. For example, while most participants completely agreed that possessing skills to apply research findings in practice and knowledge about research methodologies are necessary for developing as a scholarly practitioner, they did not agree that having access to higher education (e.g., MSc. PhD) is a necessary condition. This raises the question: how can these skills and competencies be taught, assessed, and supported if not through higher education? Recent studies suggest that most RTs who engage in research have learned research methodologies and developed research literacy skills through an apprenticeship-type model after graduation rather than through formal education.81,82 While this approach can be beneficial, it comes with limitations. For example, RTs may lack exposure to concepts such as methodological rigour, which may lead to problems in understanding study designs. Similarly, a limited understanding of statistical analysis can result in potential misinterpretation of statistical results. Several empirical studies have emphasized the challenges faced by RTs regarding their understanding of research methodology, their research literacy and their ability to conduct independent research.82–85 These challenges potentially hinder their ability to contribute new scientific evidence for the respiratory therapy profession.82–85 The findings of this survey underscore these challenges, emphasizing the need for future research to investigate innovative methods to support RTs in developing these skills. For example, exploring avenues such as post-professional micro-credentials or continuing professional development programs could be beneficial,86 especially as RTs often lack adequate training to engage in scholarly practice at entry-to-practice. Additionally, future research could explore what factors may hinder the pursuit of research degrees in respiratory therapy and identify novel facilitators.

Finally, respondents completely agreed that multiple affordances need to be in place to support scholarly practice in respiratory therapy, namely, having a supportive working environment, having access to resources and being allowed to participate in professional development activities, such as professional and practice working groups. These findings align with existing literature in nursing, occupational and physiotherapy, highlighting the importance of such factors.87–89 For example, some researchers indicate that manager-staff partnerships play a crucial role in translating research evidence into practice and supporting clinicians in their scholarly practice endeavours, such as participating in working groups on aspects about professional practice and in research projects.87–89 Therefore, it may be worthwhile to invest in the scholarly practice of RTs by allocating protected time, funding additional education, and providing necessary resources within respiratory therapy departments.16,90

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this work include applying a consultative and multi-stage methodology during the survey constructing process.91 Further, the survey items were developed based on previously published research by our group,20,41 built using best practices, underwent pilot testing, and was translated using best practices before being distributed.43,44,91

Nonetheless, our study has some limitations. Our response rate was low, despite including two parallel methods, frequent reminders, and incentives, which are seen to be best practices in recruitment.42,92,93 However, low response rates are not limited to this population. Survey response rates have seen a notable decline since the COVID-19 pandemic, likely due to an increase in survey studies and survey fatigue.94 Consequently, our findings may not be generalizable to the entire respiratory therapy population in Canada. Future national surveys could employ random sampling strategies to achieve a more representative sample of the profession.42 Moreover, strategies such as personalized email outreach to managers overseeing respiratory therapy departments, using online professional message board or paid advertisements on relevant professional society websites may enhance participant recruitment in this population.95

The low response rate and incomplete survey responses may also be linked to the perceived sensitivity of the general topic and/or specific items.96 For example, items about funding received, the number of published papers, or presentations given, might be interpreted as sensitive topics. Participants could be reluctant to disclose such information, possibly due to concerns about being perceived as not actively contributing to their profession and would prefer to abandon the survey.

Finally, our survey was targeted by spam bots attempting to claim the incentive rewards, despite implementing practices to prevent such occurrences. These practices included inserting a CAPTCHA security measure, incorporating reverse-coded items in the survey, and instructing distributors to share it exclusively through internal email communications rather than social media. Nevertheless, we are confident that by applying a rigorous data-cleaning protocol, we successfully mitigated the impacts of the spam bot responses on the study’s findings.

Conclusion

The results of this national survey provide a portrait of the demographic distribution, practice and scholarly profile of a subset of the respiratory therapy profession in Canada. The findings suggest a young profession with the potential for growth to meet the demands of an evolving healthcare landscape. However, there is an urgent need to build research capacity and foster a culture of scholarly practice within the profession to match the growing demands of specialized respiratory patient care. Moving forward, creating supportive environments, providing access to resources, encouraging professional development activities and creating innovative strategies to enhance the research capacity will be essential to advancing the scholarly practice of RTs.

Acknowledgements

The team would like to thank Samir Sangani, PhD for his help in creating the REDCap survey platform.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the conception or design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data. All authors were involved in drafting and commenting on the paper and have approved the final version.

Funding

MZ would like to acknowledge the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé #299965 for funding, and the Canadian Society of Respiratory Therapist Research Grant Program for additional funding. The funding body had no influence on the data collection, analysis or writing of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

MZ is deputy editor of the Canadian Journal of Respiratory Therapy, AW is an associate editor of the Canadian Journal of Respiratory Therapy, neither were involved in any decision regarding this manuscript. AB, PN, AT have no conflicts to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the McGill University’s institutional review board (study number A01-E04-22A).

AI Statement

The authors confirm no generative AI or AI-assisted technology was used to generate content.